EMNLP 2018 Highlights: Inductive bias, cross-lingual learning, and more

This post discusses highlights of EMNLP 2018. It focuses on talks and papers dealing with inductive bias, cross-lingual learning, word embeddings, latent variable models, language models, and datasets.

The post discusses highlights of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2018).

This post originally appeared at the AYLIEN blog.

You can find past highlights of conferences here. You can find all 549 accepted papers in the EMNLP proceedings. In this review, I will focus on papers that relate to the following topics:

- Inductive bias

- Cross-lingual learning

- Word embeddings

- Latent variable models

- Language models

- Datasets

- Miscellaneous

Inductive bias

The inductive bias of a machine learning algorithm is the set of assumptions that the model makes in order to generalize to new inputs. For instance, the inductive bias obtained through multi-task learning encourages the model to prefer hypotheses (sets of parameters) that explain more than one task.

- Inductive bias was the main theme during Max Welling's keynote at CoNLL 2018. The two key takeaways from his talk are:

Lesson 1: If there is symmetry in the input space, exploit it.

The most canonical example for exploiting such symmetry are convolutional neural networks, which are translation invariant. Invariance in general means that an object is recognized as an object even if its appearance varies in some way. Group equivariant convolutional networks and Steerable CNNs similarly are rotation invariant (see below). Given the success of CNNs in computer vision, it is a compelling research direction to think of what types of invariance are possible in language and how these can be implemented in neural networks.

Lesson 2: When you know the generative process, you should exploit it.

For many problems the generative process is known but the inverse process of reconstructing the original input is not. Examples of such inverse problems are MRI, image denoising and super-resolution, but also audio-to-speech decoding and machine translation. The Recurrent Inference Machine (RIM) uses an RNN to iteratively generate an incremental update to the input until a sufficiently good estimate of the true signal has been reached, which can be seen for MRI below. This can be seen as similar to producing text via editing, rewriting, and iterative refining.

- A popular way to obtain certain types of invariance in current NLP approaches is via adversarial examples. To this end, Alzantot et al. use a black-box population-based optimization algorithm to generate semantic and syntactic adversarial examples.

- Minervini and Riedel propose to incorporate logic to generate adversarial examples. In particular, they use a combination of combinatorial optimization and a language model to generate examples that maximally violate such logic constraints for natural language inference.

- Another form of inductive bias can be induced via regularization. In particular, Barrett et al. received the special paper award at CoNLL for showing that human attention provides a good inductive bias for attention in neural networks. The human attention is derived from eye-tracking corpora, which—importantly—can be disjoint from the training data.

- For another beneficial inductive bias for attention, in one of the best papers of the conference, Strubell et al. encourage one attention head to attend to the syntactic parents for each token in multi-head attention. They additionally use multi-task learning and allow the injection of a syntactic parse at test time.

- Many NLP tasks such as entailment and semantic similarity compute some sort of alignment between two sequences, but this alignment is either at the word or sentence level. Liu et al. propose to incorporate a structural bias by using structured alignments, which match spans in both sequences to each other.

- Tree-based have been popular in NLP and encode the bias that knowledge of syntax is beneficial. Shi et al. analyze a phenomenon that runs counter to this, which is that trivial trees with no syntactic information often achieve better results than syntactic trees. Their key insight is that in well-performing trees, crucial words are closer to the final representation, which helps in mitigating RNNs' sequential recency bias.

- For aspect-based sentiment analysis, sentence representations are typically computed separately from aspect representations. Huang and Carley propose a nice way to condition the sentence representation on the aspect by using the aspect representation as the parameters of the filters or gates in a CNN. Allowing encoded representations to directly parameterize other parts of a neural network might be useful for other applications, too.

Cross-lingual learning

There are roughly 6,500 languages spoken around the world. Despite this, the predominant focus of research is on English. This seems to change perceptibly as more papers are investigating cross-lingual settings.

- In her CoNLL keynote, Asifa Majid gives an insightful overview of how culture and language can shape our internal representation of concepts. A common example of this is Scottish having 421 terms for snow. This phenomenon not only applies to our environment, but also to how we talk about ourselves and our bodies.

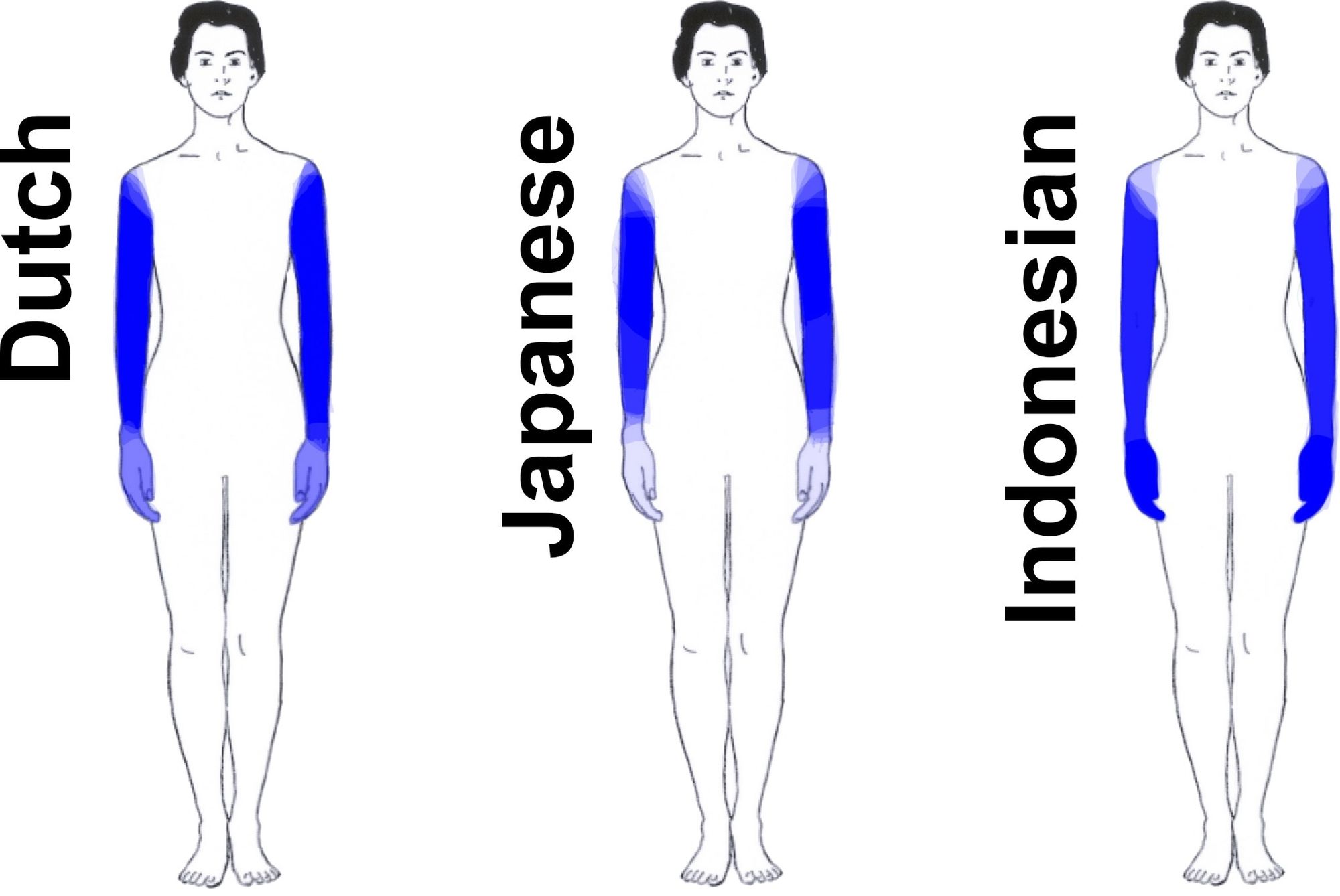

Languages vary surprisingly in the parts of the body they single out for naming. Variations in part of the lexicon can have knock-on effects for other parts.

If you ask speakers of different languages to color in different body parts in a picture, the body parts that are associated with each term depend on the language. In Dutch, the hand is often considered to be part of the term 'arm', whereas in Japanese, the arm is more clearly delimited. Indonesian, lacking an everyday term that corresponds to 'hand', associates 'arm' with both the hand and the arm as can be seen below.

The representations we obtain from language influence every form of perception. Hans Henning claimed that "olfactory (i.e. related to smell) abstraction is impossible". Most languages lack terms describing specific scents and odours. In contrast, the Jahai, a people of hunter-gatherers in Malaysia, have half a dozen terms for different qualities of smell, which allow them to identify smells much more precisely (Majid et al., 2018).

There was a surprising amount of work on cross-lingual word embeddings at the conference. Taking insights from Asifa's talk, it will be interesting to incorporate insights from psycholinguistics in how we model words across languages and different cultures, as cross-lingual embeddings have mostly focused on word-to-word alignment and so far did not even consider polysemy.

- For cross-lingual word embeddings, Kementchedjhieva et al. show that mapping the languages onto a third, latent space (the mean of the monolingual embedding spaces) rather than directly onto each other, makes it easier to learn an alignment. This approach also naturally enables the integration of supporting languages in low resource scenarios. (Note: I'm a co-author on this paper.)

- With a similar goal in mind, Doval et al. propose to move each word vector towards the mean between its current representation and the representation of the translation in a separate refinement step.

- Similar to using multilingual support, Chen and Cardie propose to jointly learn cross-lingual embeddings between multiple languages by modeling the relations between all language pairs.

- Hartmann et al. analyze an observation of our ACL 2018 paper: Aligning embedding spaces induced with different algorithms does not work. They show, however, that a linear transformation still exists and hypothesize that the optimization problem of learning this transformation might be complicated by the algorithms' different inductive biases.

- Not only word embedding spaces induced by different algorithms, but also word embedding spaces in different languages have different structures, especially for distant languages. Nakashole proposes to learn a transformation that is sensitive to the local neighborhood, which is particularly beneficial for distant languages.

- For the same problem, Hoshen and Wolf propose to first align the second moment of the word distributions and then iteratively refine the alignment.

- Alvarez-Melis and Jaakkola offer a different perspective on word-to-word translation by viewing it as an optimal transport problem. They use the Gromov-Wasserstein distance to measure similarities between pairs of words across languages.

- Xu et al. instead propose to minimize the Sinkhorn distance between the source and target distributions.

- Huang et al. go beyond word alignment with their approach. They introduce multiple cluster-level alignments and additionally enforce the clusters to be consistently distributed across multiple languages.

- In one of the best papers of the conference, Lample et al. proposes an unsupervised phrase-based machine translation model, which works particularly well for low-resource languages. On Urdu-English, it outperforms a supervised phrase-based model trained on 800,000 noisy and out-of-domain parallel sentences.

- Artetxe et al. propose a similar phrase-based approach to unsupervised machine translation.

Word embeddings

Besides cross-lingual word embeddings, there was naturally also work investigating and improving word embeddings, but this seemed to be a lot less pervasive than in past years.

- Zhuang et al. propose to use second-order co-occurrence relations to train word embeddings via a newly designed metric.

- Zhao et al. propose to learn word embeddings for out-of-vocabulary words by viewing words as bags of character n-grams.

- Bosc and Vincent learn word embeddings by reconstructing dictionary definitions.

- Zhao et al. learn gender-neutral word embeddings rather than removing the bias from trained embeddings. Their approach allocates certain dimensions of the embedding to gender information, while it keeps the remaining dimensions gender-neutral.

Latent variable models

Latent variable models are slowly emerging as a useful tool to express a structural inductive bias and to model the linguistic structure of words and sentences.

- Kim et al. provided an excellent tutorial of deep latent variable models. The slides can be found here.

- In his talk at the BlackBox NLP workshop, Graham Neubig highlighted latent variables as a way to model the latent linguistic structure of text with neural network. In particular, he discussed multi-space variational encoder-decoders and tree-structured variational auto-encoders, two semi-supervised learning models that leverage latent variables to take advantage of unlabeled data.

- In our paper, we showed how cross-lingual embedding methods can be seen as latent variable models. We can use this insight to derive an EM algorithm and learn a better alignment between words.

- Dou et al. similarly propose a latent variable model based on a variational auto-encoder for unsupervised bilingual lexicon induction.

- In the model by Zhang et al., sentences are viewed as latent variables for summarization. Sentences with activated variables are extracted and directly used to infer gold summaries.

- There were also papers that proposed methods for more general applications. Xu and Durrett propose to use a different distribution in variational auto-encoders that mitigates the common failure mode of a collapsing KL divergence.

- Niculae et al. propose a new approach to build dynamic computation graphs with latent structure through sparsity.

Language models

Language models are becoming more commonplace in NLP and many papers investigated different architectures and properties of such models.

- In an insightful paper, Peters et al. show that LSTMs, CNNs, and self-attention language models all learn high-quality representations. They additionally show that the representations vary with network depth: morphological information is encoded at the word embedding layer; local syntax is captured at lower layers and longer-range semantics are encoded at the upper layers.

- Tran et al. show that LSTMs generalize hierarchical structure better than self-attention. This hints at possible limitations of the Transformer architecture and suggests that we might need different encoding architectures for different tasks.

- Tang et al. find that the Transformer and CNNs are not better than RNNs at modeling long-distance agreement. However, models relying on self-attention excel at word sense disambiguation.

- Other papers looks at different properties of language models. Amrami and Goldberg show that language models can achieve state-of-the-art for unsupervised word sense induction. Importantly, rather than just providing the left and right context to the word, they find that appending "and" provides more natural and better results. It will be interesting to see what other clever uses we will find for LMs.

- Krishna et al. show that ELMo performs better than logic rules on sentiment analysis tasks. They also demonstrate that language models can implicitly learn logic rules.

- In the best paper at the BlackBoxNLP workshop, Giulianelli et al. use diagnostic classifiers to keep track and improve number agreement in language models.

- In another BlackBoxNLP paper, Wilcox et al. show that RNN language models can represent filler-gap dependencies and learn a particular subset of restrictions known as island constraints.

Datasets

Many new tasks and datasets were presented at the conference, many of which propose more challenging settings.

- Grounded common sense inference: SWAG contains 113k multiple choice questions about a rich spectrum of grounded situations.

- Coreference resolution: PreCo contains 38k documents and 12.5M words, which are mostly from the vocabulary of English-speaking preschoolers.

- Document grounded dialogue: The dataset by Zhou et al. contains 4112 conversations with an average of 21.43 turns per conversation.

- Automatic story generation from videos: VideoStory contains 20k social media videos amounting to 396 hours of video with 123k sentences, temporally aligned to the video.

- Sequential open-domain question answering: QBLink contains 18k question sequences, with each sequence consisting of three naturally occurring human-authored questions.

- Multimodal reading comprehension: RecipeQA consists of 20k instructional recipes with multiple modalities such as titles, descriptions and aligned set of images and 36k automatically generated question-answer pairs.

- Word similarity: CARD-660 consists of 660 manually selected rare words with manually selected paired words and expert annotations.

- Cloze style question answering: CLOTH consists of 7,131 passages and 99,433 questions used in middle-school and high-school language exams.

- Multi-hop question answering: HotpotQA contains 113k Wikipedia-based question-answer pairs.

- Open book question answering: OpenBookQA consists of 6,000 questions and 1,326 elementary level science facts.

- Semantic parsing and text-to-SQL: Spider contains 10,181 questions and 5,693 unique complex SQL queries on 200 databases with multiple tables covering 138 different domains.

- Few-shot relation classification: FewRel consists of 70k sentences on 100 relations derived from Wikipedia.

- Natural language inference: MedNLI consists of 14k sentence pairs in the clinical domain.

- Multilingual natural language inference: XNLI extends the MultiNLI dataset to 15 languages.

- Task-oriented dialogue modeling: MultiWOZ, which won the best resource paper award, is a Wizard-of-Oz style dataset consisting of 10k human-human written conversations spanning over multiple domains and topics.

Papers also continued the trend of ACL 2018 of analyzing the limitations of existing datasets and metrics.

- Text simplification: Sulem et al. show that BLEU is not a good evaluation metric for sentence splitting, the most common operation in text simplification.

- Text-to-SQL: Yavuz et al. show what it takes to achieve 100% accuracy on the WikiSQL benchmark.

- Reading comprehension: Kaushik and Lipton show in the best short paper that models that only rely on the passage or the last sentence for prediction do well on many reading comprehension tasks.

Miscellaneous

These are papers that provide a refreshing take or tackle an unusual problem, but do not fit any of the above categories.

- Stanovsky and Hopkins propose a novel way to test word representations. Their approach uses Odd-Man-Out puzzles, which consists of 5 (or more) words and require the system to choose the word that does not belong with the others. They show that such a simple setup can reveal various properties of different representations.

- A similarly playful way to test the associative properties of word embeddings is proposed by Shen et al. They use a simplified version of the popular game Codenames. In their setting, a speaker has to select an adjective to refer to two out of three nouns, which then need to be identified by the listener.

- Causal understanding is important for many real-world application, but causal inference has so far not found much adoption in NLP. Wood-Doughty et al. demonstrate how causal analyses can be conducted for text classification and discuss opportunities and challenges and for future work.

- Gender bias and equal opportunity are big issues in STEM. Schluter argues that a glass ceiling exists in NLP, which prevents high achieving women and minorities from obtaining equal access to opportunities. While the field of NLP has been consistently ~33% female, Schluter analyzes 52 years of NLP publication data consisting of 15.6k gender-labeled authors and observes that the growth level of female seniority standing (indicated by last-authorship on a paper) falls significantly below that of the male population, with a gap that is widening.

- Shillingford and Jones tackle both an interesting problem and utilize a refreshing approach. They seek to recover missing characters for long vowels and glottal stops in Old Hawaiian Writing, which are important for reading comprehension and pronunciation. They propose to compose a finite-state transducer—which incorporates domain information—with a neural network. Importantly, their approach only requires modern Hawaiian texts for training.

Other reviews

You might also find these other reviews of EMNLP 2018 helpful:

- Claudia Hauff lists 28 papers that stood out to her, focusing on dataset papers or papers with a strong IR component.

- Patrick Lewis provides a comprehensive overview of the conference, covering many of the tutorials and workshops as well as highlights from each session.

- A group of PhD students and postdocs at the University of Copenhagen wrote another very comprehensive overview of the conference.